A Sense Of Déjà Vu

2007

29 x 20 cm

150 pages

200 copies signed/numbered

There are many cities in one city and many histories within one history: this was part of the lessons of Guy Debord – if he wanted to give any.

To drift, to go with the flow: all these words have a passive connotation and such a connotation is simply wrong in the case of the dérive, which is a particular, intense kind of action. It is similar to the action of the poet who does not need to show off that he is a poet, or a photographer who does not need to show off that he is a photographer.

It is not an action of finding something, for finding something suggests that there is a searching subject who traces something that is already there. Jeremie Boyard has a distinct way of not beeing the searching kind of subject. He is not curious but attentive; he is not dissecting but sensing; not analytically inducing or deducing but adding.

His actions come close, as closely as possible, to the realm of the virtual: real in its existence, but not yet actualized. Boyard’s work is active, here, in action in order to actualize virtual objects, histories, shapes and relations.

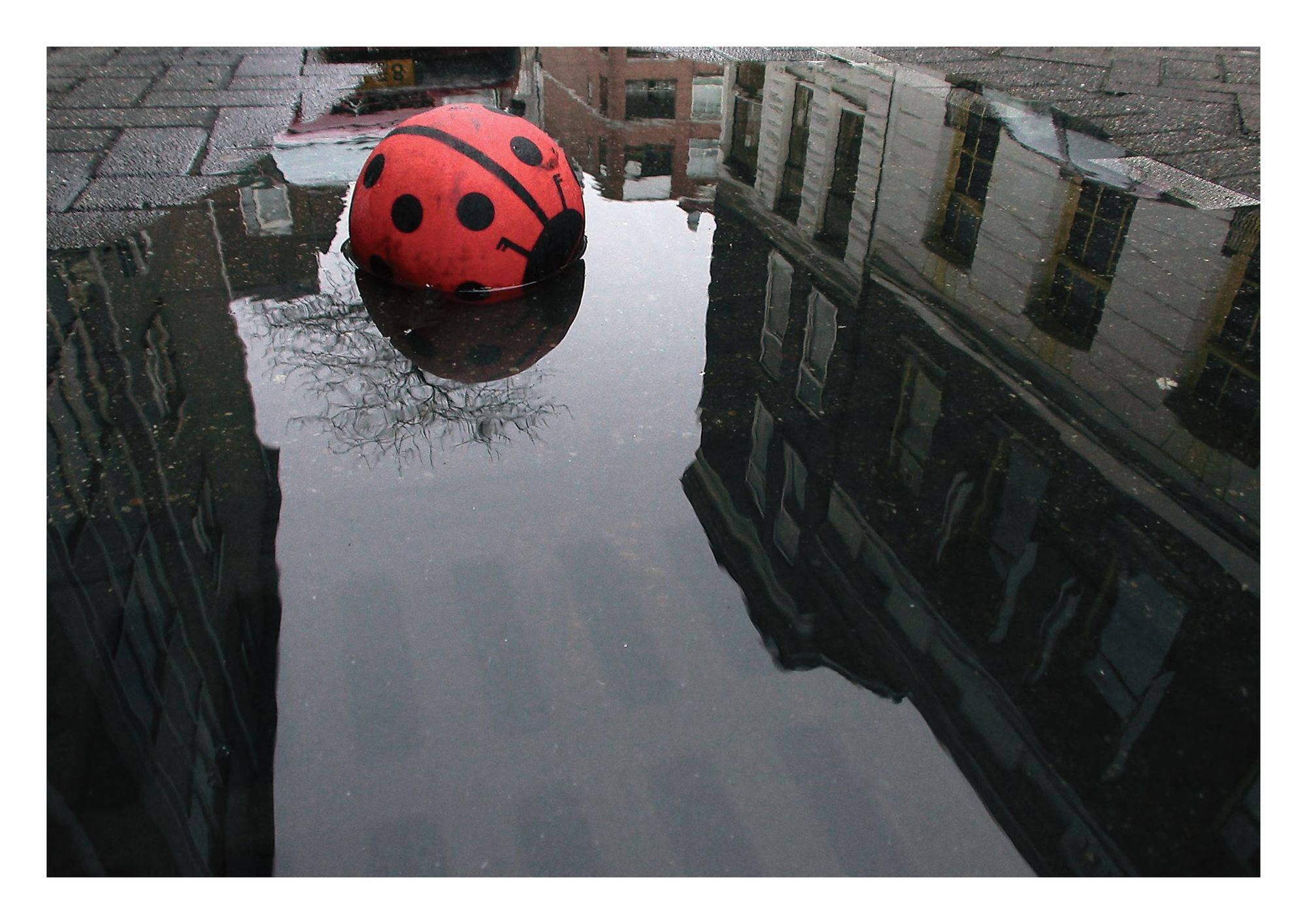

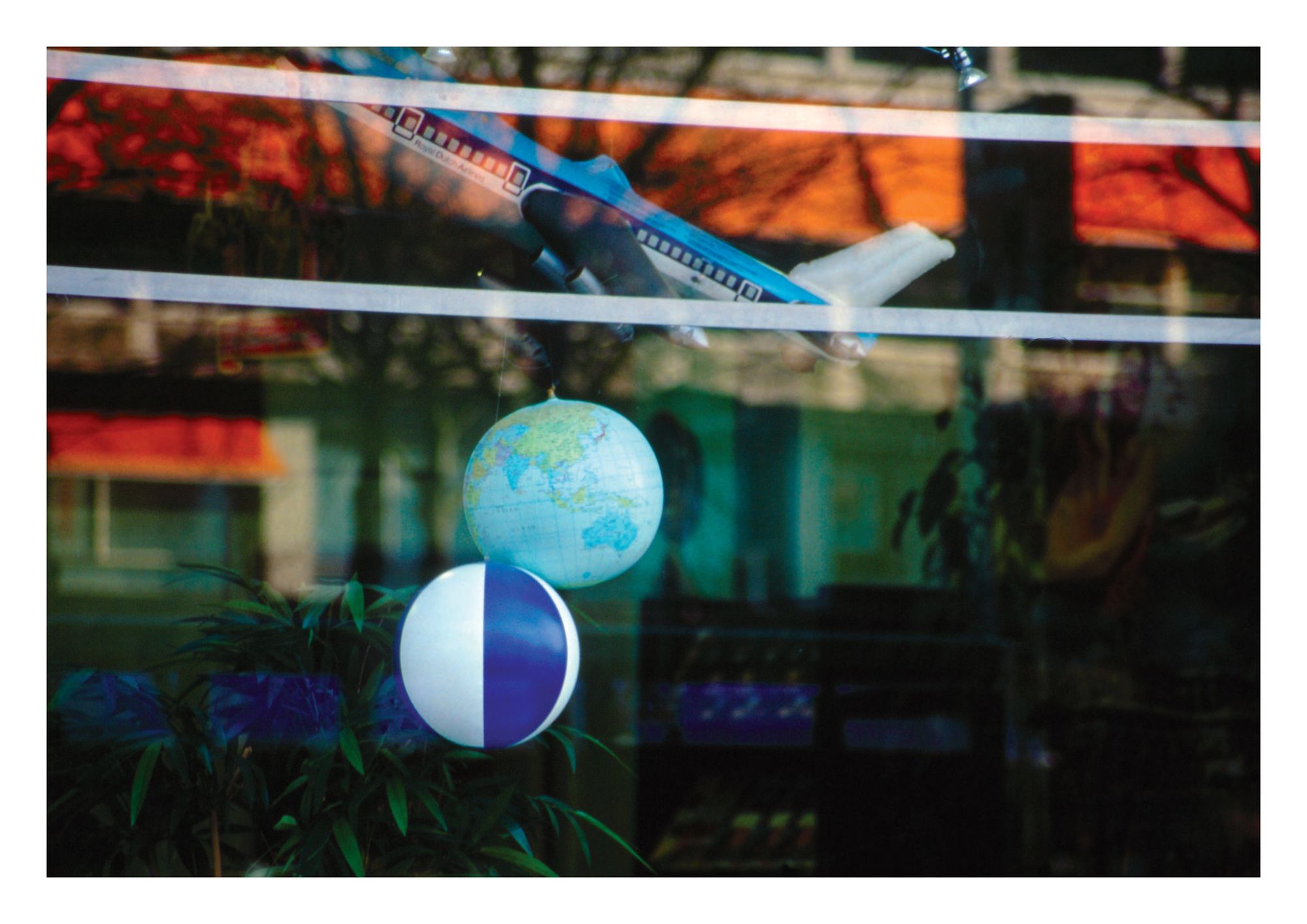

Utopia has come to mean, on average, a world in the future: a world that we project as an ideal world and that we then long for. Boyard’s work, if it is concerned at all with the idea of a utopia, presents the riddle of non-places that suddenly become places at the moment one enters them, or they enter you – these places that are not other but are always directly next to us, in front of us, touching us: this becomes possible, for instance, in boyard’s work A sense of déjà vu.

In a rhythmic flow of photographs that are remarkable in themselves, as singularities, life becomes intensified, multiplied but not dispersed. Again: Boyard’s work is not about longing or nostalgia, It’s radically. intelligently, affecionately and attentively, about being here.

Frans-Wilem Korsten

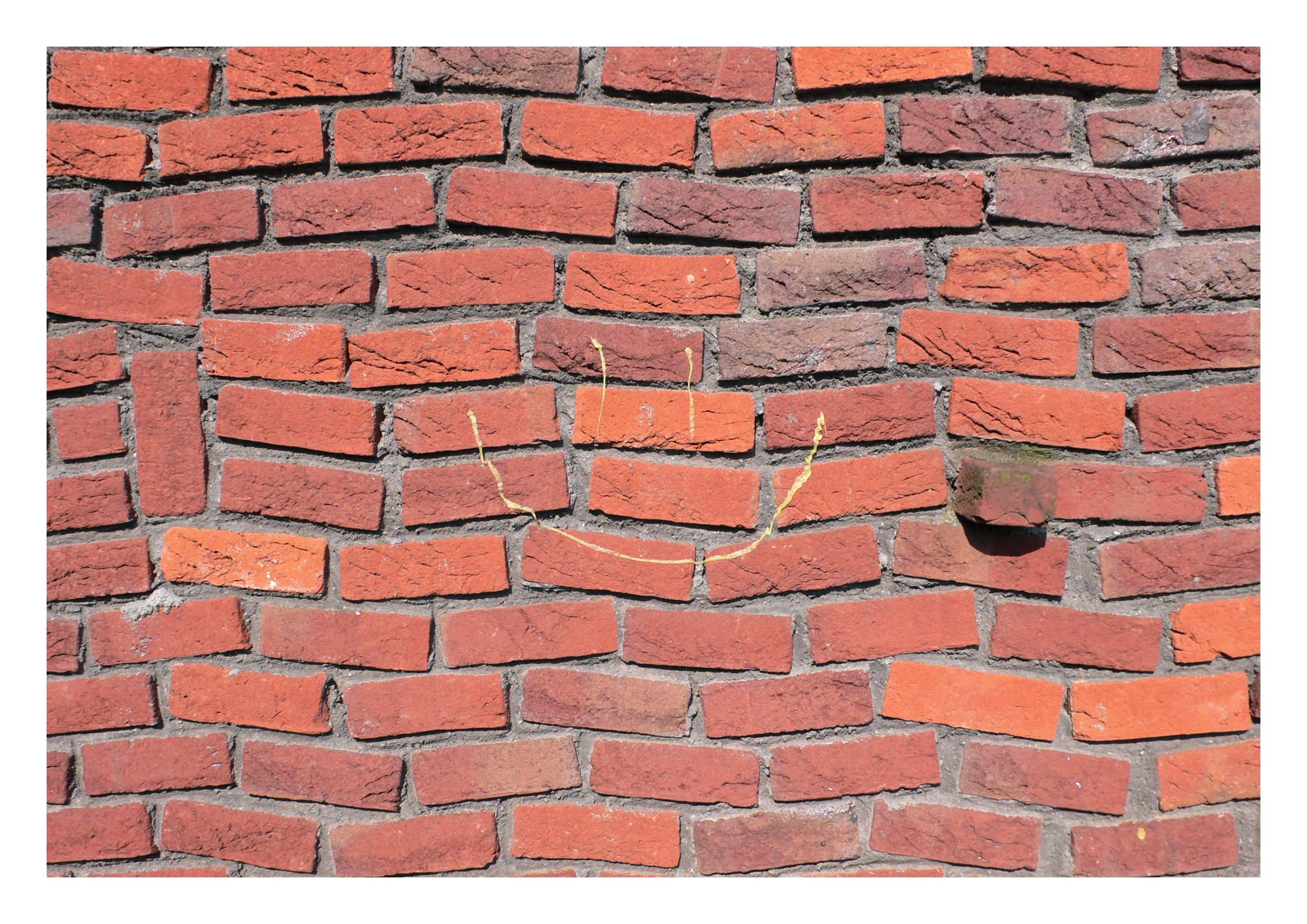

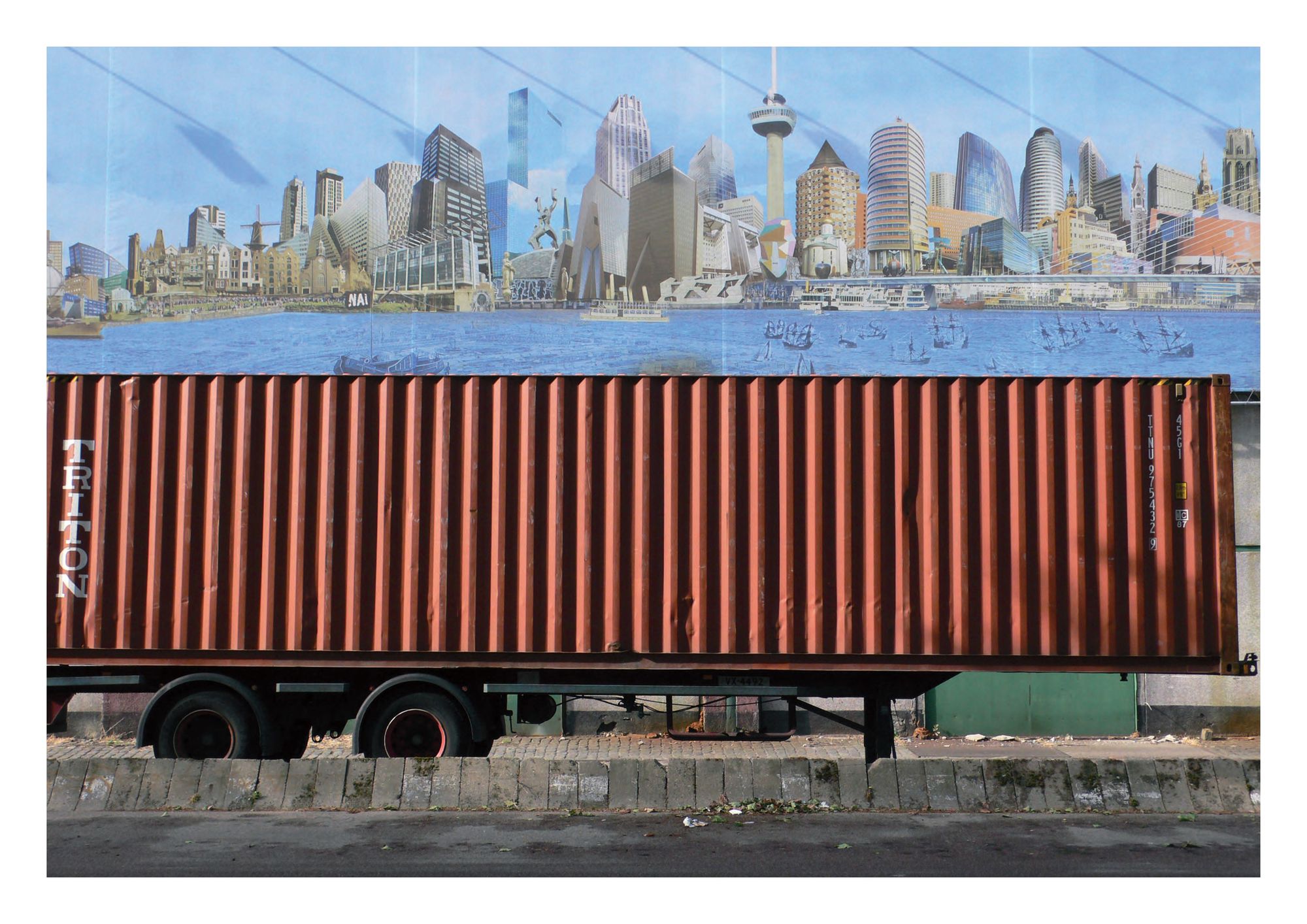

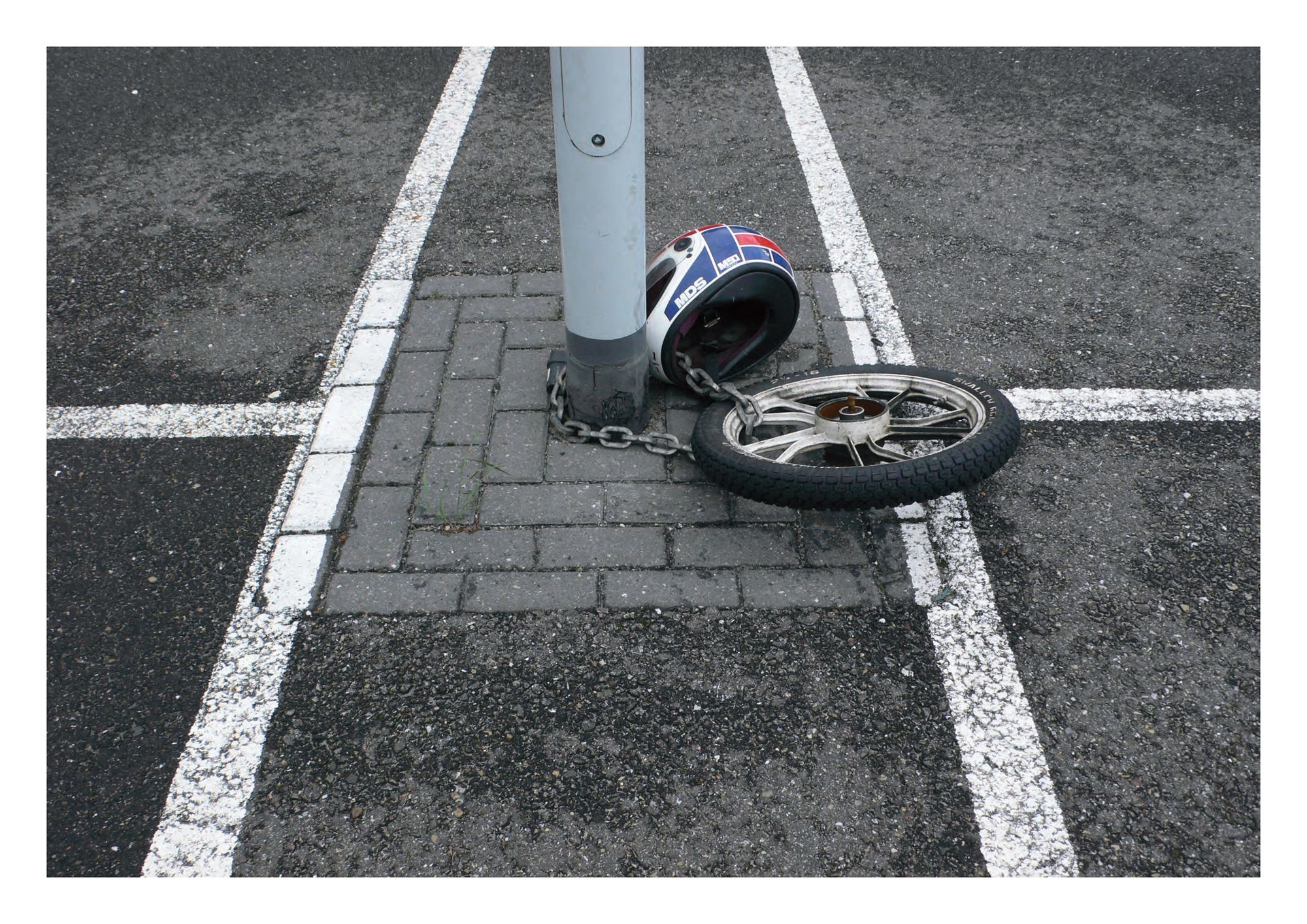

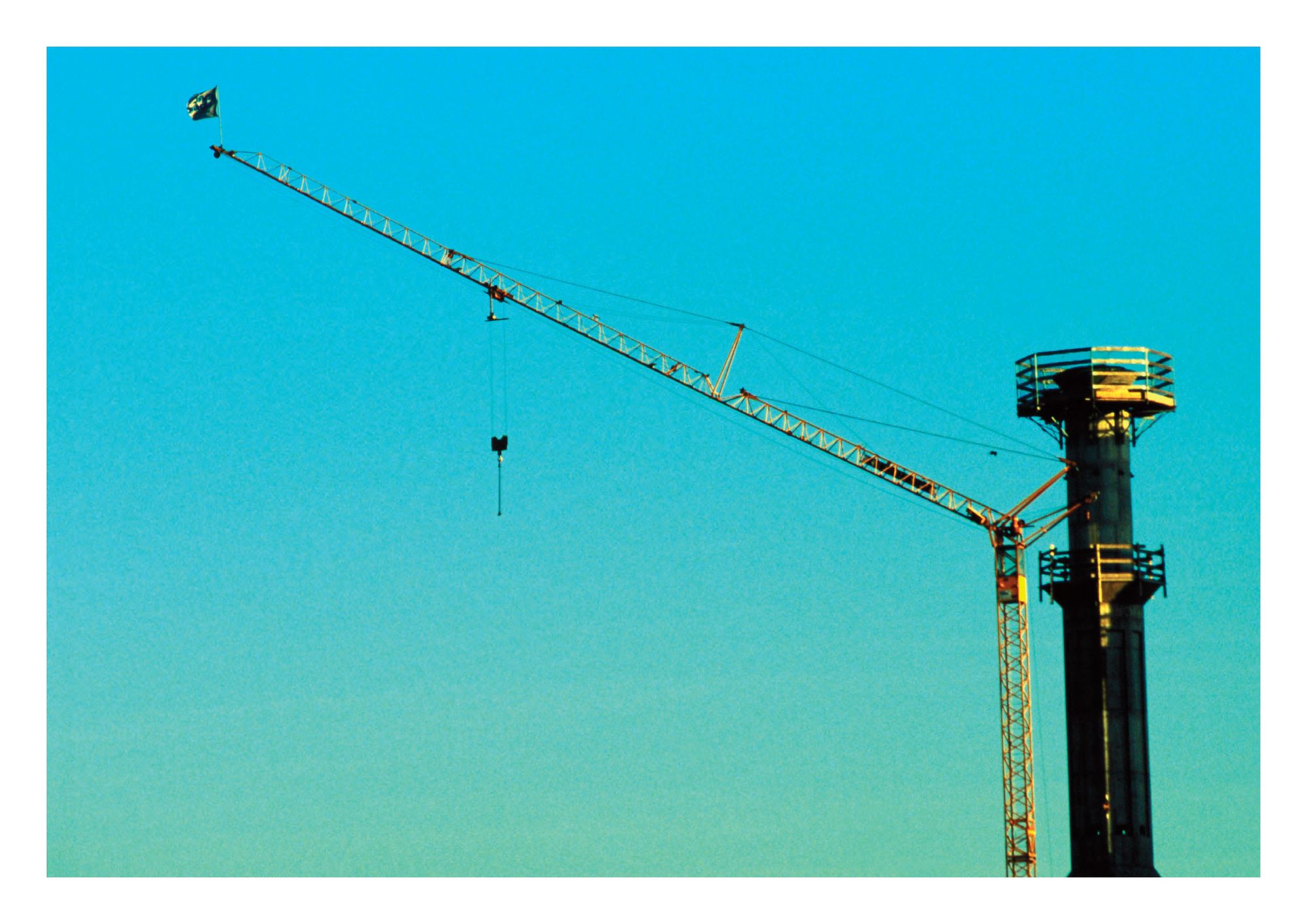

My investigation started by collecting visual impressions and traces of Rotterdam’s surface, adopting the spirit of an architectural case study, indexing guerrilla uses of the city and random detritus. I was willing to press into service a new glance which would essentially be defined by a modest, small, precise gesture, in the tradition of the street photographers, putting the standardized signs that one doesn’t notice on the order of the day. Stating a gesture of an accumulated whole, which through its accretion would gain importance.

The project’s nature was to look in a different way at the urban surroundings by taking a lot of pictures of the everyday, recording singular elements from the barrage of sensory information in the city. Using the camera as a notebook I conducted a visual research project of urban street territory unveiling embedded social conditions and contradictions. The drafting of the codes through which the contemporary city naturally expressed itself, I had in mind to illustrate the discovery of new uses for objects trough a photographic representation such as freezing behavioural acts, anonymous signs, processes of customization, adaptation and communication, dysfunctional things, specific objects and jerry-rigged attempts to fix them followed one another.

I was interested in how people cope at the street level. To act like an ethnographer doing fieldwork means you concentrate on the most normal and common objects that strangely enough are, due to their ordinariness, beyond perception. Engaging yourself in a ‘participant observation’, which means that you participate as much as possible in local daily life, while also carefully observing everything you can about the people in their cultural context and in a relatively small-scale environment. You are working somewhere in between urban structures and individual existence, organic and re-improved emerging systems, situated beyond the sophisticated economy and below a level of recognition, where people look everyday without perceiving them anymore. Obliging myself to view a system through the eyes of the user and to recognize, formalize and categorize the changing common visual vocabulary gathered in the setting as detailed photographic field notes.

Sometimes I knew that a particular single image was beautiful and interesting, but due to the nature of the project, an individual image couldn’t exist in its own right, but rather in a series of analogies where evidences of patterns were defined and where I could start looking at its relation to the other images. Exactly like the Russian Constructivist pioneer Aleksander Mikhailovich Rodchenko, who believed that multiple snapshots of Lenin rather than a single format portrait best captured the soviet leader’s personality.

J.Boyard, Rotterdam, June 2007